During the years 1960-1970, the world witnessed the emergence of the Arabic Peninsula petro-states and their defining themselves as the new regional powers. They claim an opposition from the old centers: Cairo, Beirut or Damascus. Open to the world, supporter of new technologies, these new powers are ran by a new generation that advocates an Arab culture that would be transnational and non-religious. This is a generation with powerful, progressive and intellectual ideas.

During the years 1960-1970, the world witnessed the emergence of the Arabic Peninsula petro-states and their defining themselves as the new regional powers. They claim an opposition from the old centers: Cairo, Beirut or Damascus. Open to the world, supporter of new technologies, these new powers are ran by a new generation that advocates an Arab culture that would be transnational and non-religious. This is a generation with powerful, progressive and intellectual ideas.

When there is a clash between ages, architecture can be seen as a mediation tool able to bring back together ultra-modernity and religious tradition. In terms of heritage, the East has its own codes and values, different from those of the West. However, it is hard to follow codes in these new cities without context, especially when these codes are to be reinvented. One can then wonder:

What will local identity be like for these new cities aiming not to have a context and that are threatened by the specter of global homogenization?

Dubai is a symbol for consumerism. Its birth was allowed by globalization, consumer society and the megalomania borne by a rising petrodollar. Thus, it embodies a key moment of global history. The same goes for its architecture. Dubai is a large-scale consumer good; it goes higher and higher, gets more and more expensive, more and more high-tech. What happens to its buildings when new patterns and new records outdistance them?

In a city whose architecture is destined to be ephemeral, do people seek to preserve it? Should they preserve it?

Martin Becka’s work on the ‘reappropriation of a fantasized past’ offers an archeology of Dubai’s present time. For these shots he uses an old photography technique that helps immortalize today’s city and aims at contemplating the present in the eye of the future. It displays a Dubai losing local and temporal identity. Its showcased façade architecture, traducing its will to be appealing to the eyes of the world, is not attached to what the buildings contain. The link between envelope and agenda is blurred and what the city reflects no longer matches its reality.

Can architecture exist regardless of the sites and their uses? Is a city’s heritage not linked to what it contains? What lies inside Dubai’s architectural hidden side?

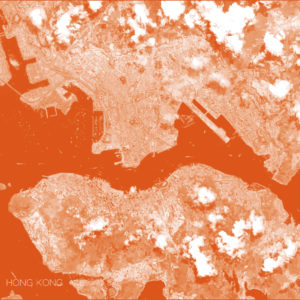

Hong Kong’s urban landscape is unique in the world. Density, dynamics and diversity are distinctive features to this oriental jewel. Former British colony since 1842, it then turned into a city-state after being transferred to China in 1997. Although it deeply reflects a Chinese culture, 155 years of British influence make it utterly different from other cities in Popular Republic of China.

Hong Kong’s urban landscape is unique in the world. Density, dynamics and diversity are distinctive features to this oriental jewel. Former British colony since 1842, it then turned into a city-state after being transferred to China in 1997. Although it deeply reflects a Chinese culture, 155 years of British influence make it utterly different from other cities in Popular Republic of China.

Located in the Southern coast of China, at the mouth of the Pearl River, Hong Kong is a strategic place for Asia. Nearly all of China’s international exchanges transit through it. This situation explains its rapid development in the beginning of the 1950s and globalization, around the blossoming of textiles trade. In the years 1970s Hong Kong’s economic development continues, mainly around finance. It becomes a city of services, a land welcoming expatriates from all over the world, and the question of its legacy faces matters of identity. The tight ‘expat’ bubble’ in Hong Kong’s island is now running away from the excessive property prices and settling in the New Territories inside the mainland, in order to improve their quality of life and get in touch with Chinese culture.

What identities for a city torn apart between internationalization and local culture?

Third financial center, Hong Kong is famous for its skyscrapers so countless that they seem to all touch each other. Since the years 1970s, tertiary economy generated a peculiar architectural heritage. Organized in multiple layers, it advocates a diversity of interlinked uses.

What are the codes to this new heritage? How will Hong Kong’s dependency on finance markets shape its evolution?

With a density that notoriously beats all records, Hong Kong is home to Mong Kok district, most densely populated territory worldwide. Another type of verticality accounts for this urban structure: its natural relief, sometimes up to 3100 feet. These highlands are seldom built and extremely protected, to the opposite of the coastal urban strip. When compared, these two types of landscape give the city a singular structure. Density and verticality result from the will to create an artificial controlled territory, where functional layers of modernism interact and shape a vertical town. Unity is made upward and surface no longer depends on the hold on the ground.

Does the scarcity of grounds make people cherish space more? In some places, density is no longer proportional to development. Does excess carry its own limits?

No Comments